On January 2nd, 2025, the digitalised archive concerning the adjudication of suspected Nazi collaborators in The Netherlands during WWII was published. The digital archive immediately received extensive traffic. What is the context of the archive, and why are people so interested?

The CABR

The Centraal Archief Bijzondere Rechtspleging (CABR) is an archive dedicated to the special judiciary created to try and convict people who collaborated with the German occupation in the Netherlands during World War II. To efficiently convict those who had worked together with the Nazi-German regime, a special branch of judiciary was created. This archive contains the names of 300.000 people who were connected to these trials. The archive contains 3.8km’s worth of documentation. Although this information had been available earlier, on January 2nd, 2025, this archive was digitally published and made largely accessible online.

The CABR contains complete and extensive information of all persons connected to the post-WWII trying and convicting of Dutch collaborators. As such, the archive initially also contained the names of people called in as witnesses and people who were suspected but later deemed innocent of treason. To refer to the CABR as a ‘traitor’s archive’ is therefore untrue.

Dutch collaboration during World War II

Following the Nazi-German invasion of The Netherlands on May 10th, 1940, and the bombing of Rotterdam on May 14th, The Netherlands capitulated and became occupied by the Nazi-German regime. Unlike France, Belgium, or Denmark, The Netherlands were placed under ‘civilian governance’. From an administrational standpoint, The Netherlands were part of the German Third Reich, whereas Belgium was ‘simply’ militarily occupied by Nazi-Germany.

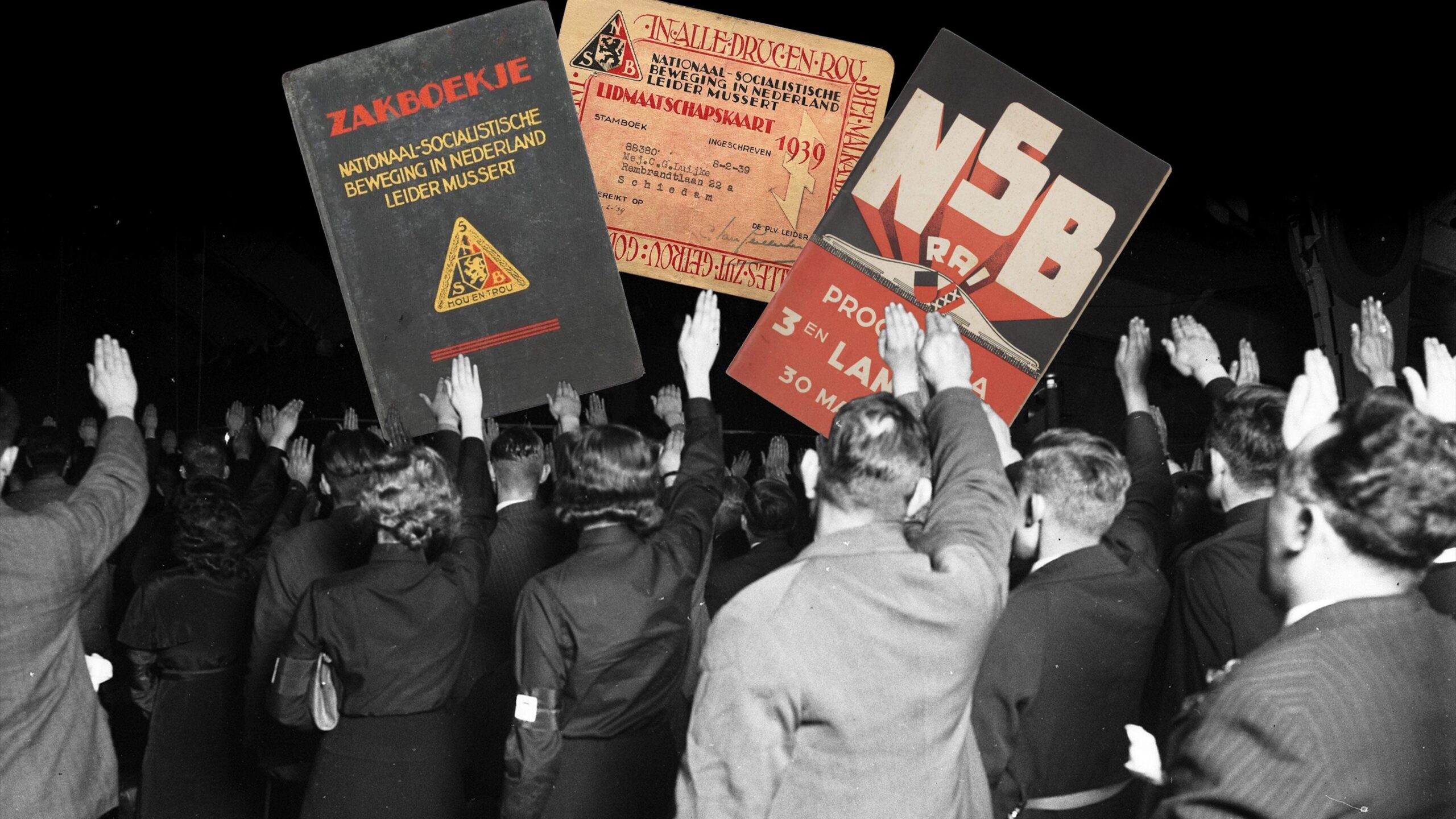

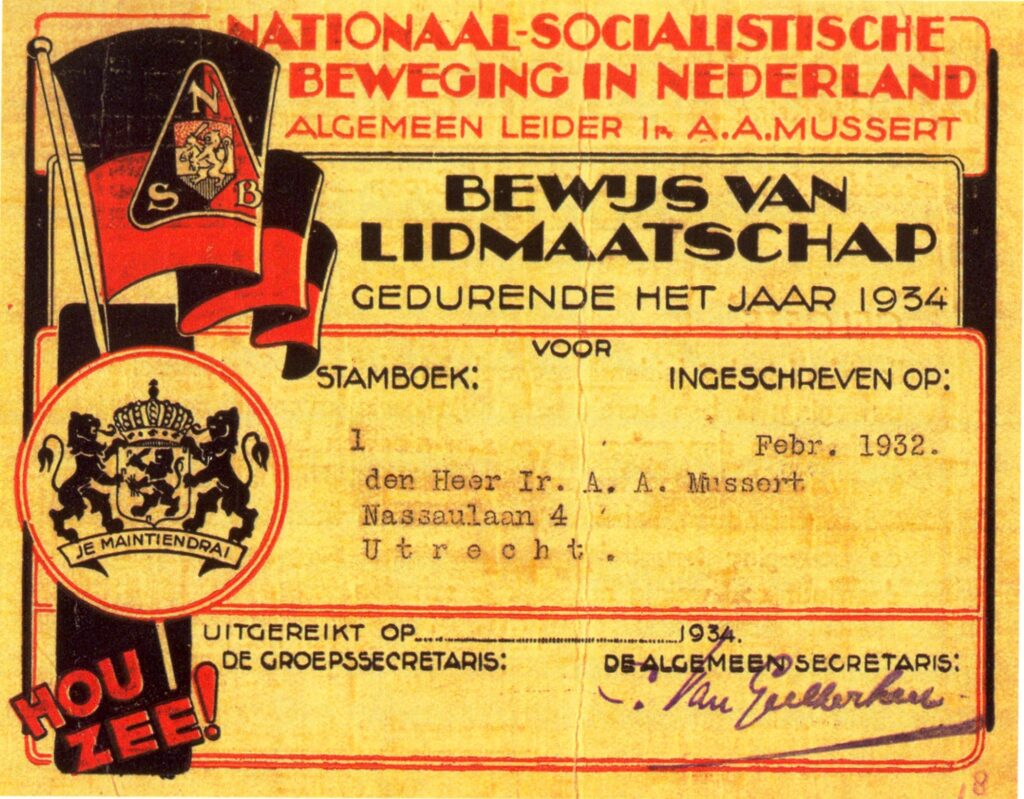

Following the occupation, the Nazi-ideology was gradually implemented and enforced. All political parties were deemed illegal except for one. The Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) became the ruling party in The Netherlands. The NSB can best be described as the Dutch version of the NSDAP, Hitler’s Nazi party. Members of the NSB were placed in prominent jobs at the lower levels of governance, such as mayoral duties. It should be noted however that national governance of the occupied Netherlands remained strictly in the hands of the German regime. Membership of the NSB often went together with various ways of assisting the Nazi’s, most notably by the betraying of Jews. Membership to the NSB is often tied to opportunism, as the betraying of Jews in hiding was often done for a financial incentive. To this day, an NSB’er is still a popular term used to refer to a traitor in Dutch speaking.

Given the close racial bond between Germany and The Netherlands, Dutch men were also encouraged to join the Waffen-SS. An elite volunteer military corps that took part in some of the most prominent fighting during WWII and was present as guards at the various concentration camps.

Why there is so much interest in the archive

After the war, the special judiciary work that was conducted to try and convict collaborators was documented. This has now been collected and digitalised. Although initially controversial in nature, a limited level of the documentation was published on January 2nd of this year. To avoid new controversy, and to avoid risks pertaining to privacy, people would have to visit the archive in person to receive the complete information. That being said the online archive is already quite extensive. Shortly after the publication, the website became inaccessible due to high traffic, and appointments to access the files in person have been overbooked. What has caused this massive peak in interest.

For many, the archive serves as an emotional turning point. Younger people might find it hard to grasp. The war ended roughly 80 years ago…who cares? But for many, their parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles directly experienced the war or the immediate aftermath of it.

Following the liberation of The Netherlands on May 5th, 1945, after jubilation, but also initial revenge against known traitors, Dutch society focussed on the enjoyment of freedom and the rebuilding of the country. The last part of the war had been devastating, especially in the cities, after rough winters and an extreme scarcity, which had people use all available resources to stay warm and somewhat fed. There was simply no time to think about the social ramifications.

Known collaborators experienced a period of exclusion, which was also felt by their innocent children. Beyond exclusion, there was a clear taboo on what had been done during the war. In tandem, the next generation experienced the glorification of the resistance heroes, leading to a popular misconception that practically all Dutch people were either part of the NSB or part of the resistance. In reality, both NSB and resistance constituted no more than 5% of the population each.

What Dutch society was left with, was a culture of uncertainty, silence, and misconceptions. Thanks to the archives becoming accessible in this manner, people have been able to properly understand their, sometimes complicated, family past. The archives have helped people to understand why their parents would never speak about their past, people discovered the true nature of their immediate family, and holocaust survivors gained some much-needed clarity.

Making these archives digitalised has been a major project. As said previously, the documentation of the CABR extents to 3.8km’s. Modern technologies such as A.I. have assisted in what has become a strong database that will assist in the breaking of taboos, and the learning of important lessons. War is not about being a hero or a villain. War is not black or white. War is about survival. It can be said that the work done to digitalise this archive, will be instrumental in the healing, understanding, and learning about the greatest tragedy in modern history.

To learn more, visit www.oorlogvoorderechter.nl to access the archives.