It is going to be a busy year for democracy. In Europe alone there will be more than 20 elections, including a European Union election. It will be an important year, but also a challenging year, in which democracy could be reinvented. As something of an appetizer, the first major election in a Western country occurred in late 2023, with parliamentary elections in The Netherlands.

When the Dutch government fell in the summer of 2023, elections were scheduled for November. The four-party coalition, collapsed over issues related to refugee asylum. How high the stakes were for the upcoming elections became clear when Prime Minister Mark Rutte announced that he would no longer lead the liberal VVD party. “In the past few days, there has been lots of speculating on what motivates me. The only answer is: The Netherlands. My position is in that regard irrelevant” Rutte said in his announcing statement to the Tweede Kamer, the Dutch House of Representatives. Mark Rutte is the longest serving Prime Minister the Netherlands has ever known, and one of the longest serving leaders in European history. After 14 years, the Dutch would get a new leader.

Many new faces

In the wake of Rutte’s announcement, a complete reshuffle would follow, with other party leaders resigning and new parties being formed. A major change in the Dutch political landscape was the unification of the Green-Left party and the socialist workers party. The two parties joined hands, as well as names, continuing as GroenLinks-PVDA, and managed to get renowned EU commissioner Frans Timmermans to lead the party in the upcoming elections. The Farmers’ party, BBB, meanwhile steadily gained traction due to the unresolved issues and general lack of representation by the government. A new party, Nieuw Sociaal Contract, was created by the immensely popular Pieter Omtzigt, who offered a more attractive alternative to the declining christian democratic party CDA, which had long been one of the top governing parties.

And the winner is…

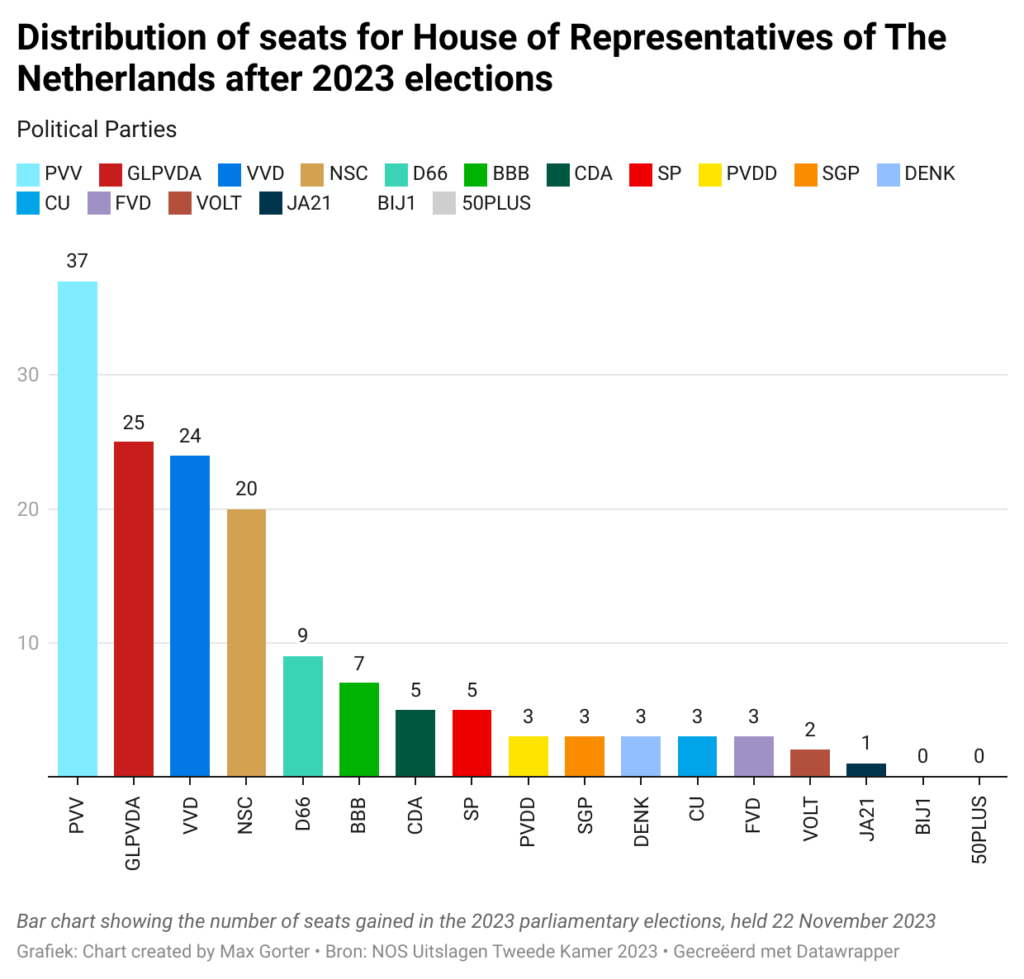

The stage was set for an exciting election with major changes possible. So, who won? Well, none of the above. In what many consider to be a great surprise, it was Geert Wilders and the Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) who won the elections, gaining 37 seats in the parliament of 150, recording the largest win by a party since the 2012 elections. With all the changes of the political landscape, any changes to Wilders’ party had gone largely unnoticed by the public. In an otherwise hectic climate, the populist freedom party stayed largely stable. Geert Wilders is best known for his anti-immigration stance and strong anti-Islam rhetoric. Internationally, Wilders has aligned himself with Rassemblement National of Marine le Pen, and the Austrian FPO.

The PVV has always been a major player in the opposition, with a sizeable number of seats. However, due to the far-right ideals, many have refused to cooperate with the PVV in terms of governance, both with the coalition and with other parties in the opposition. But the days of isolation seem to be over. How did Wilders’ party win, and why now? As said before the stability in times of chaos could be seen as a driving force. There is not a single major party that has not undergone a change in leadership, except for the PVV. The media has also seen changes in the polls as Wilders’ rhetoric became less radical in its goals, and ideology. (Temporarily) not pursuing the banning of Mosques was one of the major and most influential concessions that was made after a statement of open-mindedness by the VVD, who would not directly exclude the PVV. The PVV’s declining extremist public perception could also be caused by more extreme alternatives. Forum voor Democratie, led by Thierry Baudet, has become the new face of far-right extremism, making the PVV look more moderate in comparison.

A shift to the right

The major win of the PVV came as a surprise for the Dutch population. But was it really that surprising? Many European countries have experienced a slide to the right. In countries like Hungary, Poland, Italy, France, Austria, and of course the Netherlands, the far-right have either gained in popular support or have already won a major election. With the increased popularity of the populist far right, we should not consider it unlikely that more right-wing gains will be made in this busy year of elections. With the wellbeing of democracy in mind, the win of the PVV leads to some tough dilemmas. Many of the statements and plans of the PVV are aimed towards the ‘de-Islamisation’ of the Netherlands. Wilders has long promoted the banning of the Quran and is passionately against the open borders of the EU. A small bit of research shows that there are many of Wilders’ plans and views that are at the least immoral, and at the most, unconstitutional. And while Wilders has toned down his views and has expressed his wish to be (if allowed) a “Prime Minister for all the Dutch people”, the reality is that his views can be seen as undemocratic. Through the functioning of the Dutch electoral system, Wilders could be side-lined in the formation of a government. Something the most avid haters of Wilders are hoping to see happen. What that entails however is the exclusion of a party that has won the popular vote, which is undemocratic too. The ascension of Wilders’ PVV shows the duality of democracy and forces us to reflect on what we see as democracy. Is democracy the representation of the people, with all results being good as they are made by the people, or is democracy’s function to defend the greater good and institutional rules that aim to protect the people?